“Our lives are attended by a remarkable beauty, a beauty that extends to the dark things. I have come to see that light and darkness are dependent on each other. There is a tenderness that emerges when you come to love both. ” – Adam Wolpert, environmental artist

Survivors of genocide suffer traumatic experiences unknown to most of us. Art may help us understand. But making art from other people’s trauma can be both ethically challenging and emotionally draining. On study tours to Rwanda and Uganda artists learn to bear witnesses to the stories they hear from survivors. The first step is to master the art of silent, compassionate listening.

A TENDER EMBRACE OF THE DARK SIDE

by Lydia Breen

On a summer evening in 2008, four young Ugandan women sit outside their classroom under the glow of a single battery-powered light bulk, talking to a small group of visiting playwrights about the 20-year reign of terror they experienced under the Lord’s Resistance Army.

“It was a theatrical setting,” said dramatist and teacher Erik Ehn who organizes study tours to promote conversations between artists and survivors of mass violence. The trips are a collaborative project between California Institute of the Arts and the Interdisciplinary Genocide Studies Center in Rwanda (IGSC).

The four Ugandan students belonged to a group of of war orphans and former child soldiers who had been traumatized by Uganda’s brutal war waged by the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA).

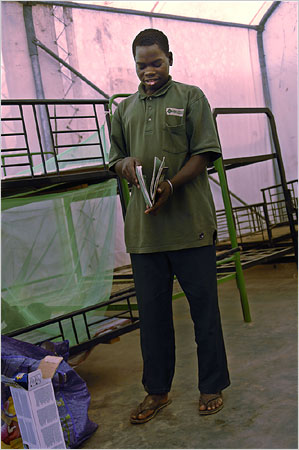

Anea Grace (who is not connected to this story) was abducted and forced to have a child with an LRA commander. She was shot in the leg while escaping. Credit: V.Vick, NYTimes

“They were members of a community of people who had experienced trauma at a level unknown to the rest of us,” said Ehn, explaining that the headmaster at the school encouraged his Ugandan students to testify as part of their healing process. Still, Ehn remembers feeling uncomfortable with the encounter:

“We heard these very harrowing stories. It was not the first time the students had told them. But there was something about me that felt like a butcher. It was abrupt, brutal and incomplete but not entirely inappropriate.”

Conversations begun on the tours continue at the Arts in the One World Conference held at the California Institute of the Arts in the United States to help artists, students, teachers and scholars discuss how to make art in times of extremity. At this year’s conference ( January 21-24, 2010) the group explored the challenges artists face writing about the traumatic testimonies of survivors.

Ehn says that survivors’ testimonies can help the outside world understand what people have been through. But artists would do well to receive these testimonies with humility and respect. The first step is to act in a way that invites a person to talk. The process of silent, compassionate listening can help survivors believe in themselves and be themselves.

Director and writer Emily Mendelsohn was a Cal Arts student when she visited the Ugandan school with Ehn and others. Now an alum, she co-teaches a class to prepare students for future trips. She says one of the main goals of the tours is create opportunities for artists to hear survivors’ stories first-hand. “There is directness in sitting down to say: ‘I want to hear your story and you want to tell it. Our role is to listen to what happened to people and learn where they are now. We aren’t there to solve problems.”

What are her own recollections of the meeting with the four Ugandan women?

“I have a memory of images, faces and bodies. It’s a feeling that is very heavy,” she says. “It was an intimate encounter, but it didn’t lead me to feel that I knew these girls, that I could appreciate the fullness of their experience.”

"Christopher Oyet (who is not connectedto this article) was kidnapped at age 9 and forced to help with the killings. 'Now, I am scared of myself,' he said." credit: Vanessa Vick. NY Times

How can an artist bear witness to a testimony when he or she can not fully understand what the survivor went through?

Mendelsohn says it is this kind of question that keeps her returning to the region. (This summer will be her fourth trip.)

Ehn, who was dean of the School of Theatre at Cal Arts and now heads the playwriting program at Brown University, says the process of using art to document trauma can be a difficult undertaking. It may yield imperfect results, but it is important to try.

“We can’t accept that atrocity is unspeakable,” Ehn says. To do nothing is “to allow tyrants to triumph.

Although the tours can provide only a partial glimpse into the human toll of extreme violence, they allow participants to stand face-to-face with survivors and try to understand what they have been through.

Ehn drew on his memories from the Ugandan school to write Dogsbody, his new work about force and trauma, told from the point of view of child soldiers. The play takes a journey to a world of unending violence and war, where two child soldiers hack their father to death and another child uses a human head as a soccer ball.

A dog in a genocidal circumstance is grotesque. I know that dogs are to be deeply feared. – Erik Ehn

Drawing on themes from The Iliad, Ehn says his play “doesn’t take on the cause of violence. It is about violence itself, violence that is unredeemed and unexamined. It’s about the damage. “

Mendelsohn directed a partial reading of Dogsbody at the 2010 Arts in the Once World Conference. In the first act of the play (“Trauma Ward”) she says Ehn draws on the stories from Uganda to take a journey of the mind, to create an emotional landscape where the normal markers, including one’s sense of time and one’s trust in other people, have been removed.

Playwright and Cal Arts alum Deborah Asiimwe was also on the Ugandan trip. Her new work, Forgotten World, was informed by the testimonies she heard there. Asiimwe, who is from Uganda, says the play looks at a variety of conflict situations where children forced to become soldiers and sex slaves.

Pictured: Playwright Deborah Asiimwe. A reading of her play "Forgotten World" will take place on May 21st at 7:00PM in N.Y.C. at The Public Theater during the NEW WORK NOW reading series.

“It’s not just about Uganda,” she said. “It could also be about southern Sudan or Darfur or the streets of L.A. – any place where children are forgotten.” Ethical concerns were very much on her mind at the time she was writing the piece. She remembers hearing about a conceptual artist who paid people in a poor village in Central Uganda to legally change their last names to that of the artist in exchange for a goat or a pig. The artist then exhibited the pictures he took of the villagers holding up their new identity cards, all with his last name.

“I remembered thinking this is not right,” she said. “I started questioning my own art, questioning how art has turned these stories into a commodity. I asked myself: ‘How can I as an artist tell these stories without taking center stage?’ I don’t have the answer yet. But I know there has to be a responsible way to tell someone’s story.”

Tens of thousands of child soldiers have been recruited to fight in all regions of the world. Most are under the control of non-state armies.

Forgotten World was produced at Cal Arts in 2009 and directed by Obie award-winning actress and director Laurie Carlos. The final scripting and staging involved an unusual degree of collaboration between the writer, director, cast and crew, a multi-ethnic group who brought their own experiences with to the production. Asiimwe says she felt extremely supported as an artist. “It was the best gift that Cal Arts gave me,” she said.

A few month later, when Asiimwe started working on a re-write of the play, she reported feeling like she did when she was struggling with the first drafts: “I’m back to having strange nightmares…dreaming of guns…getting into my own world again. Emotionally and physically, I find myself being a witness alone, as opposed to witnessing collectively.”

Genocide separate peoples from the things they hold dear - family, home, culture, community. Testimonies of their experiences can help the outside world understand what they have been through and, in some cases, how the world has failed them. Credit: V. Vick, NYTimes

Artist who tackle war and extreme violence in their art may find the task daunting. But Erik Ehn says they should try. If words seem inadequate to describe the experience, he suggests discarding language and trying something else – or experimenting with different points of view:

“If you are writing about rape, you can describe it or you represent it, ” he says. “You can replace the rape with something else. If you are doing that, you might as well make it as creative – like ripping a paper in half.”

Erik Ehn was dean of the School of Theatre at Cal Arts until 2009. He now heads the playwriting program at Brown University and continues to collaborate with Cal Arts and the IGSC in Rwanda. Credit: Kagami

Television images can sometimes be emotionally overwhelming. He says, “You can’t compete with the event itself or with the news reports. You can write about your own sense of helplessness. Or see..what your helplessness looks like… Beckett never writes: ‘I don’t know why I am alive.’ He shows how that thought affects his mind.”

The wages of genocide are manifest in the stories of survivors. Their testimonies shine a light on our collective conscience. Artists who allow themselves to be transformed by these stories may find themselves on a difficult creative path. But Ehn believes it is worth the effort. He says life (like art) “is at essence a dialogue.” The place to begin is to embrace survivors with tender silence.

“Silence is the most perfect gesture of inclusion. It is like the darkness of the theatre.” -Erik Ehn

*************************************

Lydia Breen is a freelance writer and filmmaker who worked with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in Switzerland for more than ten years. In 1991 she made the first film for an international audience about the effects of war on children. The film drew heavily on the testimonies of child soldiers from Mozambique. She went on to interview, write and make films about child soldiers and other children living under armed conflict in Sri Lanka, Somalia, South Africa, Liberia, Sierra Leone, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Afghanistan.

With the exception of Somalia, which is a failed state, the United States is the only member of the U.N. that has not ratified the 1989 Convention on the Right of the Child. In 2002, the U.S. did sign certain Optional Protocols which obliges it to afford certain protections to child soldiers.

To date, children in Afghanistan and Pakistan continue to be held in detention by the U.S. military.

Children should not be prosecuted for war crimes: Omar Khadr was ten years old when his family moved from Canada to Afghanistan where they lived in Osama Bin Laden’s inner circle. When he was 15, he allegedly threw a genade that killed a medic with the U.S. Special Forces. The U.N. and human rights organizations believe that Omar was essentially brainwashed. They say child soldiers should be rehabilittated not incarcerated. (See Washington Post article, Feb. 10, 2010)

Links:

ACLU’s “Soldiers of Misfortune”

Coaltion to Stop the Use of Child Soldiers. and the

Nicholas Kristoff’s colum and excellent video on rape used as a weapon of war against women in the Congo and one courageous doctors’ efforts to help.

Brilliant work.

Pingback: Emily Mendelsohn, Fulbright Fellow, to direct Asiimwe’s “Cooking Oil” in Uganda « Cafe Libre